Yesterday I took, and passed, the Canadian citizenship test. Much like obtaining the G1 license in Ontario, I didn’t find enough information online about the process, so I thought I would share some details regarding my personal experience here.

The process to obtain your Canadian citizenship

Before delving into the details of preparing and passing the citizenship test, I want to provide you with a quick overview of the entire process:

- First you’ll need to determine if you are eligible to apply and then, if you are, apply for Canadian citizenship. You’ll need to be a permanent resident who’s been in the country long enough in order to do so.

- Wait a long time. The current processing time is, on average, about 19 months. After several months, the status of your application will change to reflect the fact that your application has been received and is now being processed. Thankfully you can check the status of your citizenship application online. At some point you might receive a notice in the mail stating that your application has been accepted. This notice doesn’t mean that you’ll become a Canadian citizen for sure; just that the CIC has verified that your application was prepared correctly and will now be further processed.

- Some time later, you’ll receive a notice to appear at a local citizenship and immigration center. This notice will tell you exactly what documents you need to bring, as well as the date and time of your meeting.

- Once you pass your knowledge and linguistic ability test, you’ll be invited to a citizenship ceremony, which will is typically attended by yourself and your family and friends. Here you’ll receive a citizenship certificate, which (it’s worth noting) cannot be used for identification purposes (as the government wants you to apply for a passport instead).

Since most people already have citizenship from a different country (in my case, Italy), it’s important to note that Canada is happy to give you citizenship even if you plan to keep your original citizenship. Dual citizenship is allowed in Canada.

Other countries however may not allow you to keep your original citizenship or may require you to go through a process to let them know about your new citizenship. Either way, this has nothing to do with Canada, and you should contact your country of origin’s consulate in Canada for questions related to dual citizenship.

Back to the topic of the citizenship test itself, in this post I focus on the third step in the process outlined above, which is the least documented one. The fourth step is really straightforward. It’s just a formal ceremony where you’ll recite the oath of citizenship, sign and receive your citizenship certificate.

On the day of your citizenship test

You may wondering what things are going to be like on the day of your citizenship test. The notice you receive in the mail prior to this day will include details of where and when you need to appear. If you foresee not being able to attend on your scheduled test date, contact the CIC (by telephone) immediately to let them know and to reschedule your test.

It’s important that you arrive on time. In my case I arrived half an hour beforehand, and I suggest you do the same to be on the safe side. Nevertheless, in my case arriving early turned out to be a moot point because the appointment was at 1pm, and the office was closed between 12pm and 1pm for lunch. (At my local Kelowna center the opening hours were 10am-12pm, and 1pm-3pm, but I’m not 100% sure that your local center will have the same hours.)

You’ll be asked to provide your notice to the clerk at the window, and then to have seat. After a while you’ll be called in for registration. This is an informal interview that should not last more than 10-15 minutes. During this interview you’ll be asked to provide the original documents of the photocopies you sent in with your citizenship application, as well as a photocopy of your passport’s biographical information (basically the first two pages).

They won’t really tell you right there, but during this short interview you’re actually being tested on your linguistic skills (whether you opt to have a conversation in English or French is up to you). The interviewer may ask you generic questions about your life, why you moved here, where you work, and so on. They should not ask you knowledge based questions at this point. This step is primarily done to figure out if your English or French is good enough for you to to become a Canadian citizen.

If your English (or French, if you chose French) is considered to be poor, you won’t be taking the written knowledge test. Instead, you’ll be scheduled to meet with a judge who will ask you knowledge questions and then make a final decision regarding whether your linguistic skills are good enough for you to be granted citizenship.

If your English (or French) is poor to the point of not being able to communicate with at least a certain degree of ease, the immigration official is, in theory, allowed to fail you as though you had failed the knowledge test (more on this topic in a moment). I don’t believe this happens very often though, as they are very understanding of linguistic challenges, but you should be able to communicate in one of the two official languages in order to obtain your Canadian citizenship.

Once this registration/linguistic test is over, you’re asked to take a seat in the waiting room. After everyone (in the room with you) has registered, you’ll be invited into a different room where the actual knowledge test will take place.

The Citizenship Knowledge test

The knowledge test is aimed at verifying your understanding of:

- The rights and responsibilities of Canadian citizens

- Canadian knowledge (history, geography, culture, political system, etc)

All the information you need to know in order to pass the test is contained within the Discover Canada guide, which is available for free in print, online, as an ebook, audiobook, and even in iPhone format. This guide is only 50 page long, but it contains a significant amount of details, names, and dates. Do not wait to open up the guide for the first time the day before the test, as this will most likely not give you enough time to adequately study and go on to pass the test.

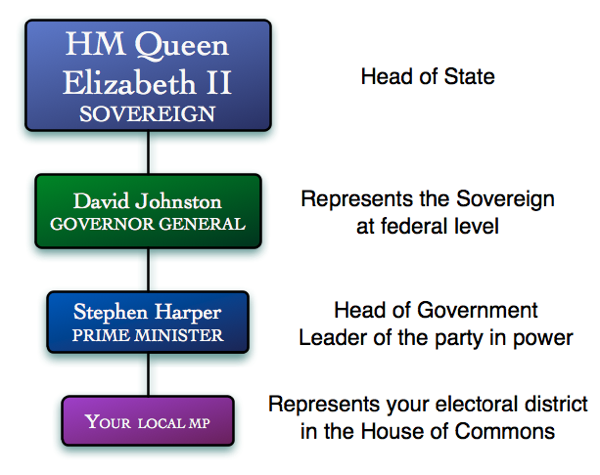

Key Federal Government Figures

The citizenship knowledge test contains 20 questions, and you are provided with 4 possible answers for each of them. You need to circle the correct answer for all of these questions on the sheet provided. If you get five or less questions wrong, you’ll pass the test. If you get six or more wrong, you’ll fail. Each applicant gets their own completely randomly generated set of 20 questions, so there’s no way to base your own test questions directly off of those someone else may have had.

The fail rate has increased over the last few years. This used to be a trivial test with a mere 5% failure rate. Today however that number has climbed to over 30%. This is to say, you’ll probably pass, but you need to actually study in order to do so. Your average Canadian citizen polled at random on these questions would not pass the test.

You are given 30 minutes to complete the test, which might not seem like that long, but to be honest, it should be plenty of time for most people. I had 19 of the 20 questions answered within two minutes of sitting down. One question’s phrasing was a bit ambiguous so I spent some time thinking about which answer was “more correct” in their view.

I don’t remember all the questions that I was presented with, but there was definitely a mix of both very basic and somewhat harder ones on the test. For example, among the basic questions, they asked me about Canada’s winter and summer sports (hockey and lacrosse, respectively), who the Prime Minister was (Stephen Harper), and who sits at the House of Commons (MPs elected by citizens to represent their electoral district).

As well I remember questions about things such as which are the Atlantic provinces (Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick), and which provinces formed the Confederation in 1867 (Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick). Topics such as what the highest honor in Canada is (Victoria Cross), who the first Prime Minister (Sir John A. MacDonald) was, and where the majority of Quebec’s population lives (St. Lawrence’s river) were also covered in my sampling of test questions.

I don’t remember the exact questions for the, supposedly more advanced questions, but I believe they delved into such things as when Nunavut became a territory (April 1, 1999), Vimy Ridge, D-Day and Juno Beach, and the names of early Canadian explorers.

Once you are done answering the questions, you leave the room and wait outside. After a little bit someone will come out to inform you regarding whether you passed or failed the test (but no score or feedback on the specific questions will be provided). If you pass, you’ll also receive a notice in the mail inviting you to attend a ceremony where you’ll take the oath and receive your citizenship certificate. In my case this will take place at the end of next month, six or so weeks after the knowledge test, but I’m sure these dates vary a lot depending on your own location.

The whole citizenship test process took about an hour and a half, but this too will depend on the number of people attending the test, how many government employees are working that day, etc.

If you fail the knowledge test, they’ll schedule an interview with a judge on a different date. The judge will ask you to prove your knowledge to see if you’re ready to become a citizen yet or not. If you are, you may receive your citizenship. If you aren’t, I believe you’ll have to reapply for citizenship from scratch (a process that takes at least a year and a half).

Preparing for the Canadian citizenship test

Since the stakes for failing the knowledge test are high, I really recommend that you study the guide in-depth before attempting the test. Personally, I made the mistake of starting to study the guide only a few days before my test. As a result, I had to cram a ton of information into a very short amount of time. Thankfully, I ended up being over-prepared for the test, which I found to be quite easy compared to some of the obscure facts I had learned (from the official guide) in preparation for the citizenship test.

Ideally you’ll want to start studying from the day that you receive the notice onwards. If you do, hopefully you’ll find the test to be easy and will save yourself a lot of last minute stress.

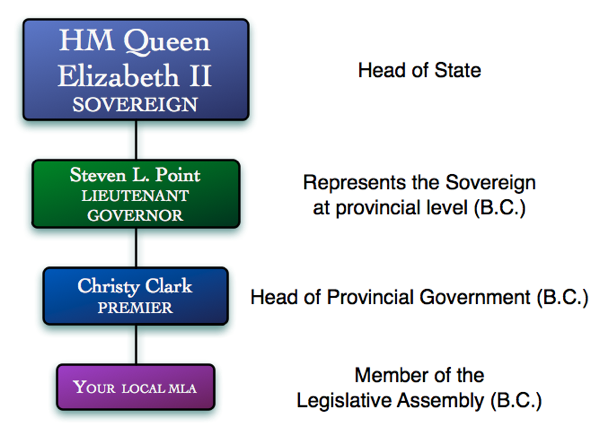

If all you do is read the guide through once, cover to cover, you’ll probably fail the test. Read/study it at least a couple of times and then take as many practice tests as you can. Also, don’t forget to look up information about key government figures in your own province or territory. I personally made sure I knew even the names of the leaders of the opposition parties at both the federal and provincial level (I knew the federal ones already, having a keen interest in politics, but I had to look up and memorize the local ones for British Columbia, the province where I now live.)

Key B.C. Provincial Government Figures

I have found the following citizenship practice tests to be beneficial. 90% of the questions on my actual citizenship test were not new to me, as I had encountered very similar ones before through these practice tests.

- Canadian Citizenship Test iPhone/iPad app by Jonathan Lum

- Citizenship Flash Cards iPhone/iPad app by Tip Top Good Studio

- Practice Tests by V-Soul

- Practice Tests by Richmond Public Library

- Workbook Canada Citizenship Test

Keep in mind that some of the answers for things that change may be slightly outdated on these tests (e.g., who the leader of the Opposition Party is), but generally speaking they do a terrific job at helping you prepare.

I truly believe that if you can pass the practice tests with ease, you won’t have a problem with the real one, as many of the sample questions are extremely close to the real deal.

Should you face a question for which you truly don’t know the answer, you can start by excluding the answers that you feel are obviously wrong. Usually you’ll instinctively feel that 2 out the 4 possible answers are wrong. If you can narrow it down to two choices, you have a 50% chance of picking the right one.

Many non-profit organizations provide free classes to help you prepare for the test as well. I went to the South Okanagan Immigrant and Community Service center for the first time a couple of days before my test, so there was no time for me to take an actual course. However I did get to have a volunteer test me on my knowledge (by asking me sample questions).

Similar organizations exist all across the country and if you contact your nearest one as soon as you receive your notice to appear (or sooner, if you want to get a lot of prep work in), you’ll be able to attend classes on the material you need to learn and will feel less like you’re on your own throughout the study process. (A list of local organizations of this kind are provided on the pinky-orange colored sheet of paper you should receive with your notice to appear.)

In conclusion, if you prepare for the test, you stand a good chance of coming out just fine. Best of luck to you, soon to be, fellow Canadian citizen.